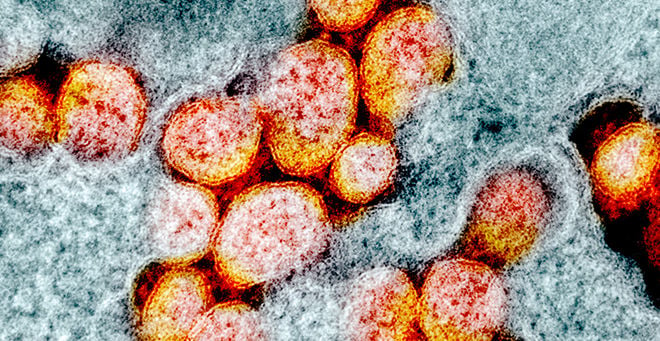

Vaccination against COVID-19 was linked to reduced inflammation in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection, according to a paper co-authored by UMass Chan Medical School researcher Jonathan M. Gerber, MD. The multicenter trial, which included an analysis of biomarkers that regulate the immune response, known as cytokines and chemokines, was published in The Lancet Microbe.

“This gave some insight into why vaccines may result in less severe disease and particularly help to prevent life-threatening complications of COVID,” said Dr. Gerber, the Eleanor Eustis Farrington Chair in Cancer Research, professor of medicine and molecular, cell & cancer biology, and director of the UMass Cancer Center. Gerber is also chief of the Division of Hematology & Oncology in the Department of Medicine.

The 21 biomarkers measured in blood samples of study participants with COVID-19 who were seen in an outpatient setting help fight off infection but also contribute to inflammation.

“Many of the complications of COVID are the inflammatory response that the body has to the virus,” said Gerber. “When you look at people who have had very, very severe infections, and particularly those who have died from COVID, they had overwhelming inflammation, particularly in the lungs.”

Gerber explained that if the infection is contained or neutralized quickly in the body, then there isn’t as much need for an intense immune response, so there is less likelihood of out-of-control inflammation and resulting damage.

In the longitudinal, prospective cohort study, blood samples from 882 patients who were enrolled at 23 outpatient sites in the United States between late June 2020 and late September 2021 were collected at screening, 14 days later and at 90 days. Patients had SARS-CoV-2 infection primarily from the alpha strain in the earlier days of the trial, or the delta strain later during the study period.

The vast majority, 78 percent, were unvaccinated; 6 percent were partially vaccinated; and 16 percent were fully vaccinated at baseline.

After adjusting for variables, concentrations of many inflammation biomarkers were significantly lower among the fully vaccinated group than among the unvaccinated group at screening, when viral loads were relatively high. On day 90, fully vaccinated participants had approximately 20 percent lower concentrations of certain inflammatory biomarkers than unvaccinated participants. All participants showed decreased cytokine and chemokine concentration over time.

According to Gerber, the study offers insight first into why people who weren’t vaccinated were more likely to be sicker or die from COVID, namely because of an out-of-control immune response. Second, he said, is that people who took a more prolonged time to clear the infection suffered a lot of lingering damage from that inflammatory response, even after they cleared out the virus. And the third possible insight, although there wasn’t data from this project to support it yet, is that the dynamics of the inflammatory response may give clues into why some people develop long COVID.

“In these more persistent types of illnesses, even after the virus is cleared, it may have triggered some longer-lived inflammatory response,” said Gerber.

Share this story