If you had a terminal illness, what kind of end-of-life care would you want? Would you ask your doctor to let nature take its inevitable course or would you fight for as much time as you could? Even when terminally ill patients have a clear idea of what they want, their wishes for end-of-life-care all too often are not adequately communicated to physicians, care givers and other health professionals, in part because there is a lack of standard documentation for care givers to follow.

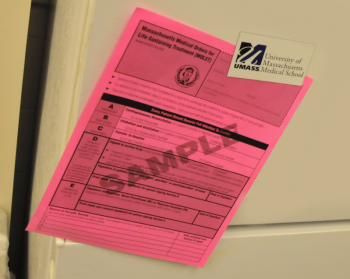

Through a pilot program known as Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (MOLST) being conducted in the Worcester area with support from UMass Medical School’s Commonwealth Medicine, health care professionals and palliative care experts are designing a process to ensure that a patient’s wishes regarding life-sustaining treatment are documented and accessible to all health care providers.

“Part of the problem is that there is no one form used to record a patient’s wishes,” said Mary A. Valliere, MD, assistant professor of medicine and a member of the Massachusetts MOLST steering committee, which was formed by a 2008 legislative act requiring the establishment of a MOLST demonstration program. “It’s not that physicians and patients aren’t discussing the implications of end-of-life care; they are. A physician might have a conversation with a patient and take notes on the patient’s wishes, but in an emergency, that information isn’t always accessible when and where it’s needed by other care givers.”

Different than a health care proxy or a living will, which are written for when the patient becomes incapacitated and cannot communicate, the MOLST form is a detailed way of communicating, in clinical terms, life-sustaining care preferences of all patients who are in the advanced stages of serious medical conditions or terminal illnesses. The pilot program is focused on educating hundreds of health care professionals, physicians, nurses and social workers, as well as patients, on how to use the forms. Once completed, the form becomes a valid medical order to be honored by anybody treating the patient: physician, nurse, emergency medical technician (EMT) or nursing home staff.

The form is filled out in consultation with a physician and copies of are accessible to all care providers through the patient’s medical records. The original, printed on bright pink paper, is intended to be taken home by patients. Dr. Valliere says patients are counseled to keep the form in a visible area of the home, such as on a refrigerator, so that EMTs and other emergency responders can quickly locate it. At the same time, Valliere’s colleagues are working with EMTs to ensure they are familiar with the form, know to look for it and understand its instructions.

Another hurdle in efficiently communicating end-of-life care to health providers, according to Valliere, is the natural variance in terms and language used by different physicians and health professionals. Different people may use different, non-clinical terms, to describe the same type of treatment or situation. To help standardize the type of care given, the form uses clear and concise clinical language that can be understood by all care providers.

“It’s our goal to create an organized and standard set of documentation that records a patient’s wishes in clinical terms that can be understood across the spectrum of care providers,” she said.

Valliere stressed that end-of-life care is an ongoing discussion the patient has with his or her physician. The document is designed to accommodate change, given that a patient’s wishes may change as his or her condition changes. “An important part of this pilot project is accounting for how a patient’s wishes for care may evolve during the course of an illness,” Valliere said. “This form is intended to document a series of conversations between a physician and a patient.”

Valliere said the committee is currently evaluating its findings on the implementation of the form, which was rolled out in April 2010. The committee’s conclusions will be incorporated into a final report, which is expected to be submitted to the Executive Office of Health and Human Services in early 2011. The Secretary of Executive Office of Health and Human Services will then make a recommendation regarding statewide adoption of the form. Valliere said she hopes to see the bright-pink forms put into wide use in the Worcester area by 2012.

To present additional information about the Massachusetts Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatmentprogram, Valliere will be the featured speaker for the Center for the Advancement of Primary Care Prime Time Conversations on Wednesday, Jan., 12, from 12:20 p.m. to 12:50 p.m. For more information on how to view the webinar, please contact Jeanne McBride, RN, in the Center for Advancement of Primary Care atJeanne.McBride@umassmemorial.org or visit the Massachusetts MOLST web site at http://www.molst-ma.org/